Long before the 1960s when L’Hexagone became the term du jour to describe the six-sided borders of Metropolitan, or mainland, France, the concept of what it meant to be French, or even speak the language of Molière, was still being defined. The contours of the country weren’t always known by its inhabitants, who often lived and died within the areas surrounding their own hamlets.

Early European maps, such as the Bronze age Saint-Bélec slab from Northwestern France, were most likely cadastral plans for marking land use and ownership. But they weren’t widely-distributed, public-use depictions that aided inhabitant’s understanding of their own environment. The growing relationship between maps - as a model of reality - and reality itself would take one family line several generations to solve.

The first time that France’s residents could view their country as a whole, and in great detail, was thanks to geometric and topographic advances which culminated in the formation of the Cassini map. It was ordered by King Louis XV, and created piecemeal, by hand, from 181 smaller maps, which required almost 70 years of work (1747 - 1815) overseen by four generations of cartographer-astronomers under the surname Cassini.

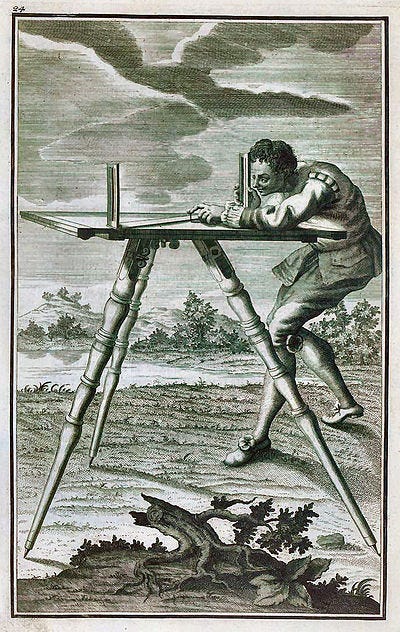

The land surveys themselves, at least as noted in the 1750s, were done by a team of between eight and 20 surveyors, who were spread out at a distance of 20 km from each other, sweeping the land from north to south. They also worked from bell towers, with local clergy and lords as guides in order to collect the names of places to be depicted on the maps. The task was made more difficult by the fact that two hamlets which shared the same topography would often have different names for the same geographical feature, such as a hill. But names weren’t the only disconnect:

When one of its geometers climbed Mont Gerbier de Jonc, “he could take in at a glance several small regions whose inhabitants barely knew of each other’s existence,” author Graham Robb writes in The Discovery of France: A Historical Geography from the Revolution to the First World War. [1]

Following a day in the field, the surveyors reviewed their notes and drafted maps in their makeshift offices. Upon return to Paris, their work continued and underwent rigorous review, before approval and subsequent engraving. The surveys as a whole were completed on the eve of the French Revolution, in the 1790s, but the last were only printed in 1815, following the fall of the Republic.

The map wasn’t only novel due to the geometric measurements - each sheet required the calculation of 300 secondary points - but also because maps up until that moment were a military endeavour, and strategically shrouded in a certain amount of secrecy. In fact, from 1793 til 1815 - the period during and following the French Revolution - the Cassini maps were confiscated and deemed for military use only, as Napoleon considered maps to be a an arme de guerre, or weapon of war.

In 1790, France replaced the Ancien Régime provinces - whose names were deeply connected with long-held loyalties - with the names of departments that reflected the geography of each region. This act of altering the nomenclature had, in part, the effect of lessening the nobility's power over the country - a country that was still not fully defined, even with the Cassini map being relatively complete.

An overview of the French borders at the time did not yet include Nice, Savoy and Corsica, but did include other towns, now part of Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany. Additionally, the Cassini family efforts revealed France to be smaller than previously believed. Louis XIV is supposed to have famously told his astronomers that they had lost him more territory than his generals had won (however the quote can’t be verified). Regardless of size, the completed maps would help with the establishment of new roads and canals, which futhered the development of trade and, as a consequence, increased the Kingdom’s coffers.

It would take over 50 years for the Cassini map to be superseded by the publication of the military staff officer map from the late 1800s, known as the Carte d’état-major. And despite the hundreds of years that have passed since the start of the project that would map the entirety of mainland France in great detail, and the advancements in technology - especially with the advent of satelites - the Cassini maps are still studied today.

Mapmaking wasn’t the only tool of the era that would aid in unifying the country, as language would play a large part - albeit through the State-sponsored stamping out of patois, or local languages. Both endeavors would arguably end up being boons for the nation but harmful on the local level, as evidenced by the following excerpt:

In the early 1740s, a cartographer taking part in the Cassini mission […] was hacked to death in a tiny village in the Massif Central called Les Estables. A savage and irrational act? Not according to Robb, who argues that these people 'were defending themselves against an act of war'. To be mapped out was eventually, over time, to be phased out of existence." [3]

Such a sentiment was data privacy for the Industrial Age, and it wasn’t exactly novel for the times. This can be evidenced in 1770’s Austria, where residents awoke one winter to find out that their houses had been numbered, and they were no longer private people but rather wards of the State, and possibly future fodder.

As historian Anton Tanter writes in House Numbers: Pictures of a Forgotten History:

A house number issued by the state…had the advantage of creating discrete, clearly distinguishable and fixed units. Once a sign was nailed on the wall of a house or painted on and left to dry, it was linked ineradicably as possible to the house. It enabled recruiting officers, tax collectors and court officials to know what was inside.

In effect, it made the walls transparent. [4]

Maps reveal who we are. They identify something sacred about us, our location, affiliations, our relationship to the land we live on. Maps can also reveal us to ourselves, providing meaning and a sense of belonging. It depends largely on how they are used and how we use them.

The decision to be mapped is not always a democratic process, as shown above, but it can be, given certain historical incentives. To be numbered and identified, to identify ourselves with a specific place doesn’t necessarily even hold true over time. Sometimes there is no “there” there, as American writer Gertrude Stein once wrote, regarding her childhood home which, upon visiting later in life, she found out no longer existed.

It’s unknown if the Cassini Map makers struggled with these deeper concepts, or if they were overwhelmed by the importance and scale of the generational project they had undertaken. One can imagine that in a 70 year period there were ample moments, perhaps late at night and after a long week, where the Cassini family - who weren’t just cartographers but also astronomers - looked up and pondered the impact of their work and imbued it with meaning.

Akin to the childhood home which served a very real purpose in its time, only to be bulldozed by progress, the Cassini Map met much the same fate. Unlike Gertrude Stein, later generations can still admire and even compare past and present.

Side note regarding the last link above:

At Geoportail (France’s online mapping service), one can superimpose a current map with the Cassini map and see what’s changed. Also, at Gallica, France’s online portal for its National Library, you can peruse the 180 grids, as well as compare them with the principal map of the time. Clicking on the text above each smaller map that appears will take you to a large zoomable version of that grid.

In order to try out the superimposition on Geoportail, click the link in question, then where it says Fonde de Carts, click Voir tous les fonds de carte, then click the Carte de Cassini option. In the settings on the right side, you can alter the opacity scale between the aerial photos and the Cassini map. The map legend is here. A full composite map is here.

Sources

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carte_de_Cassini

http://cassini.ehess.fr/fr/html/6_index.htm

https://sites.google.com/site/geohistoricaldata/data/cassini-data/demographic-data

https://french-genealogy.typepad.com/genealogie/2009/06/the-cassini-map.html

https://www.theguardian.com/science/the-h-word/2017/apr/27/cassini-the-astronomer-who-discovered-saturns-moons-and-shrank-france-history

http://www2.culture.gouv.fr/culture/actualites/celebrations2006/cassini.htm