What separates the Latin languages from one another? If they all originated from Vulgar Latin, why did they evolve into different languages? Simply put, the Roman desire to spread their culture and expand their power base - often called Romanization - brought Latin to regions that already contained speakers of other languages. In time, those languages mixed and created what is known in Romance studies as Romania continua or, more plainly, Latin Europe.

However, there are other contributing factors behind Vulgar Latin’s evolution. The presence of isoglosses, or geographic boundaries between language features, both predict and give away motives behind divisions, political or otherwise.

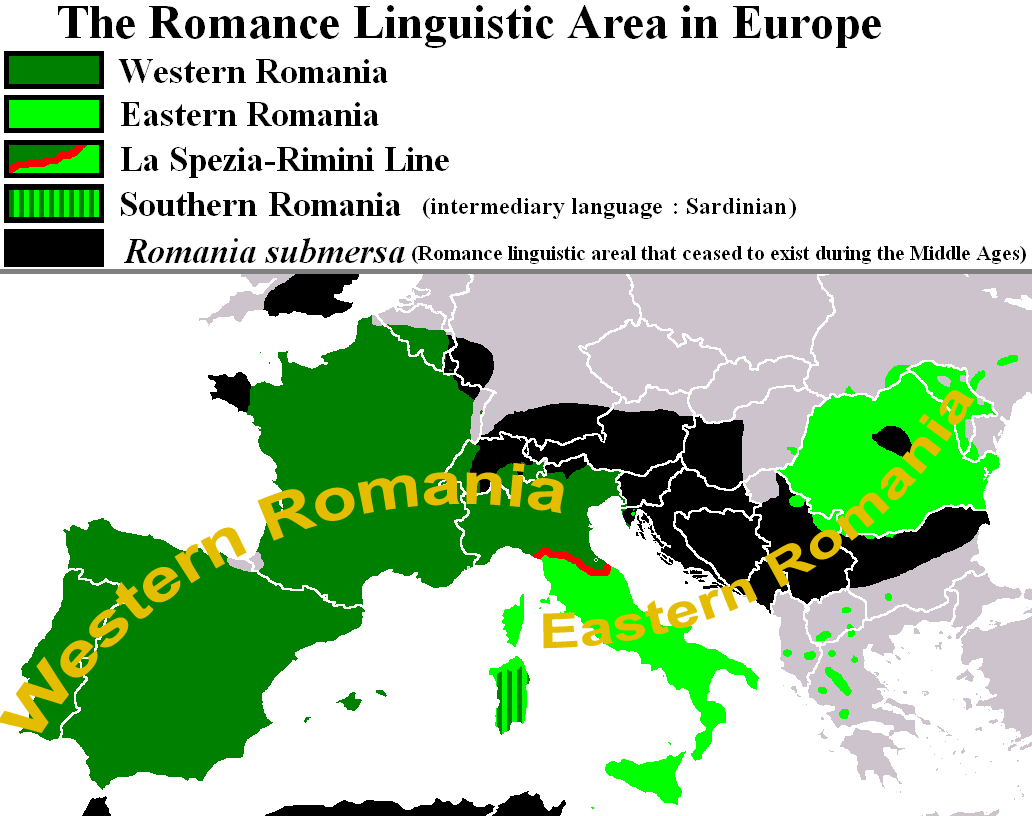

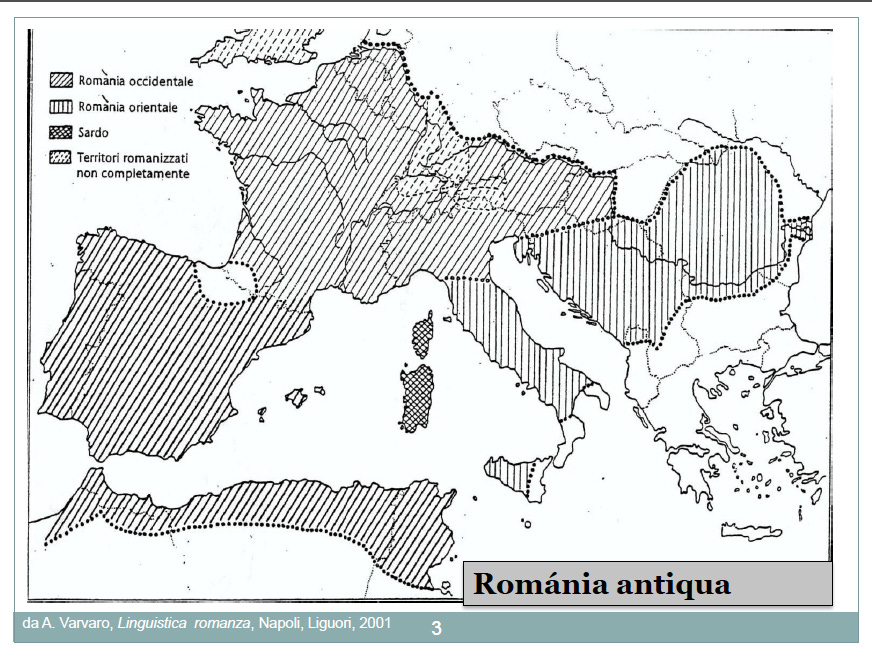

Latin Europe can generally be divided into two linguistic regions. Even the boundary for this division, which roughly runs along northern range of the Apennine Mountains in Northern Italy, has two names: the La Spezia-Rimini Line and the Massa-Senigallia Line. Regardless of one’s preferred term, the line splits the Romance languages into Western and Eastern groups, separating Spanish, French, Portuguese as well as Northern Italian dialects on one side from Central and Southern Italian dialects and Romanian on the other.

The concept was developed in 1950 by noted German linguist Walter von Wartburg after analyzing data from linguistic atlases. He looked at how Latin was influenced by non-Roman peoples. What he discovered were several important distinctions that characterized each group of languages.

These causes are to be found, according to Von Wartburg, who follows the Italian school, in the influence on Latin of the language of the peoples who preceded the Latins (Etruscans, Gauls, Iberians, etc.) and of those that succeeded the Latins (the Germanic, Arabic and Slavic conquerors.) [2]

One possible explanation for the location of the dividing line is that Gallo-Italian, made up of the languages and dialects north of the La Spezia-Rimini Line, coincide historically with the border of Cisalpine Gaul, which was inhabited by the Celts. [3, 4]

Differences

Isoglosses can be phonological or lexical in nature, that is, relating to the pronunciation or simply the use of one set of words over others. One of the main differences the Line causes is in the pronunciation of Latin ci/ce, as in centum and civitas: Italian and Romanian use the ch-sound (as in ‘church’), while most Western Romance languages use ce-sound (as in ‘center’).

Another difference is in the pluralization of nouns. To the south of the line, plurals end in a vowel while to the north they tend to end in an /s/. French is a special case, as the final /s/ is no longer pronounced (except in cases of liaison where, for example, ‘les enfants’ becomes ‘le zenfants’ in spoken French).

The third difference created by the La Spezia-Rimini Line is gemination - or the doubling of consonants - in the pronunciation of the languages below the line. Spoken Italian - which is used both below and above the line - is a bit of a special case, too, due to gemination being absent from Northern dialects. For example, the word doppio (double, in Italian) is pronounced ‘dopio’ in the north, and ‘doppio’ everywhere else. However, this is seen as a dialectal difference and not as an error to be corrected.

There are other isoglossic differences that cross the Italian landscape, albeit further south. Before the discovery of the La Spezia-Rimini Line, another German linguist, Gerhard Rohlfs, developed what he called the Roma-Ancona Line in 1937. The line distinguishes linguistic boundaries between Italy’s central and southern regions, but only in regards to the Italian language.

Curiosities

In the same way that there are isolglosses dividing a single language, that don’t coincide with differences among Latin languages as a whole, there are also many minor differences, discrepancies and curiosities surrounding the majority of points cited above. Sardinian is one such curiosity, as it is not considered to be Eastern or Western and thus doesn’t fall within the confines of the La Spezia-Rimini Line.

Sardu, as it’s known on the island, retained characteristics of pre-Roman languages yet it is also the most conservative in regards to being closest to original Latin, when compared to all the other Romance languages. Also, being geographically close to Africa, the vulgar Latin that was used on the northern part of the continent has been shown to share similarities with Sardinian, giving reason to why the island maintained a high degree of likeness with Latin.

African Romance - as the spoken Latin was known - and its subsequent disappearance, is an example of Romania submersa, or areas where the Roman Empire eventually expanded to but Romanization was initially or ultimately unsuccessful. It contrasts with Romania continua mentioned previously.

Additionally, a third term exists, Romania nova, which includes non-European territories where Neolatin languages took hold and exist til this day. Such well-known examples include the everyday use of French and Portuguese in Africa, as well as Spanish, Portuguese and French in the Americas.

Legacy

Sociolinguist Max Weinreich famously said that language is a dialect with an army and navy, but it’s rarely as clean cut as that. Political division isn’t the only causal factor, as geography can obstruct the diffusion of linguistic markers or innovations, as can migrational convergence among different peoples.

The divisions and differences among Romance languages - and within each language itself - are seemingly endless. Long after the sun set upon the Roman Empire, the manner in which the historical, political and linguistic lines have formed and held over centuries is a testament to the hegemonic polity, or the the staying power of common culture and language.

Perhaps the Third Rome, or continuation of the Roman Empire, is not the theological and political one of 15th and 16th century Russia, nor the Fascist one of the early-to-mid 20th century Italy. Perhaps it is actually something that exists and lives on, linguistically, among the more than 900 million native speakers of Romance languages.

Notes

4 - Coincidentally, a German defensive line in WWII - known as the Gothic Line - seems to follow the same boundary.