In the High Medieval period, having a fire always going in one’s home was essential for warmth and cooking. While the fire didn’t need to be at full flame, having embers hot and ready was a handy and time-saving practice. Having the ability to start a fire from those embers revolved around the action of covering and therefore preserving them and their residual heat, not only for reasons of practicality but for safety too, especially with wood and hay around as unintentional kindle.

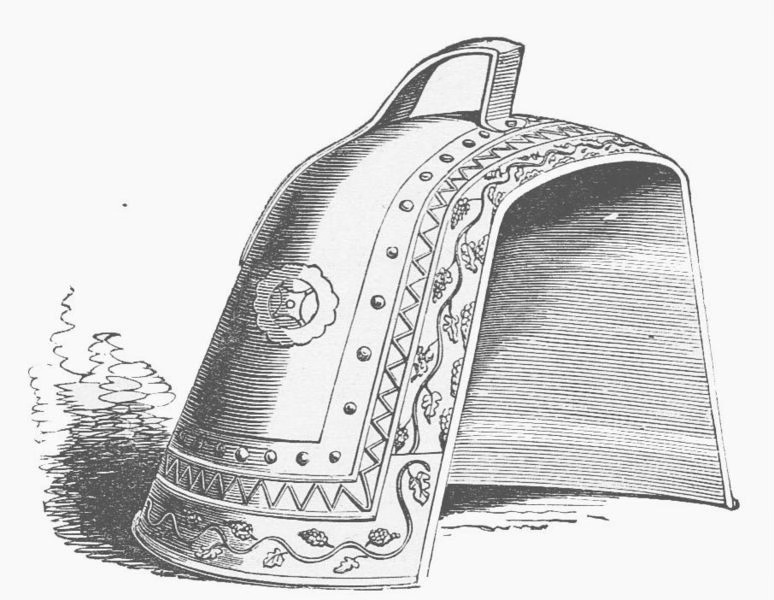

The curfew itself was a lid like construction with vented sides. This allowed the fire to be contained whilst allowing oxygen to breathe life into the embers. This meant that with the help of bellows, the fire could be brought back to life easily in the morning. The curfew could be made from various materials from unglazed terracotta clay to metal depending on the wealth of the user [1].

In France, the device used to cover the fire was literally called a “couvre-feu”, or cover fire (after the Old French carre-feu or cerre-feu). It’s hypothesized that the word “curfew” derives from this concept due to the Medieval practice of ringing of a town bell, around 8PM, to remind people to cover their fires so as not to burn down their homes and establishments while they slept [2].

A semantic shift occurred where curfew became less about covering fires and more about the town bell that was rang when people turned in for the night. Popular etymology will say this concept was initially due to William the Conqueror terrorizing the English as he invaded their lands (to prevent rebellious meetings, associations and conspiracies by night), but the practice of covering fires and ringing bells at night was already common practice across Europe at the time.

Even though 8PM might seem like an early bedtime for modern folk, the Middle Ages was a time of biphasic sleep patterns [3]. Influenced by natural light and the lack of artificial lighting, people often went to bed shortly after sunset. After waking for a few hours around midnight and engaging in all manner of mostly indoor activities - a period known as “the watch” or “the waking” - the second sleep would take place and last until morning light.

According to researcher Lionel Cresswell in a 1895 article on the origins of the word curfew, he states that there’s little to no apparent connection to fire and that it’s more likely the word derives from the medieval “third place”: carrefour (a town square or crossroads where a bell tower would normally be located) [4].

Of course, a curfew bell is most effective from a bell tower, and such edifices were born from churches going back to 400 AD. They served to summon the faithful to religious services, but also for giving an alarm when danger threatened. As a central institution of medieval towns and cities, churches have been mostly located in the town square.

Nonetheless, the modern term for curfew in two Romance languages remains a variation on “cover fire” (for example, the aforementioned couvre-feu in French, and coprifuoco in Italian). In Portuguese and Spanish, the terms differ: toque de recolha and toque de queda, which can be interpreted as “ring to gather” or “ring to stay,” respectively.

No matter the origin, meaning or the manner of employment of curfews - be it the device or directive, they can both be thought of as risk mitigation for the Middle Ages.

For another look at the history of social safety in Europe, see The Salvation of San Servolo.

Sources

1 - The History of the Curfew

2 - The Curfew Bell

3 - The forgotten medieval habit of 'two sleeps'

4 - A four-forked etymology: curfew